For three weeks, in the ghettos of the poor suburbs, euphemistically named “sensitive neighborhoods,” on the outskirts of the outskirts, thousands of cars were burned, public utilities devastated, troops of police deliberately attacked.

There is nothing new about what sparked these incidents: the absurd death of two adolescents seized by panic, in the course of “normal police behavior.” Comparable police blunders also occurred in the past, and nearly always lootings and burnings were the inevitable response. But such incidents were localized.

Nor is there is anything new in the methods employed or the visible targets: For many years now, notably in Alsace, cars are burned on New Year’s Eve or at the time of more obscure commemorations. And for a long time schools have been vandalized by schoolboys expelled from school; buses or police cars stoned; passengers methodically robbed in public transport.

What is new today is the immediate extension of this violence, its rapid spread to the provinces, well beyond the borders of a spontaneous and unpremeditated movement.

This is a movement without explicit demands, except the resignation of a Minister of the Interior disqualified by his remarks and, as everybody knows, scorned by his superiors. This is a movement impossible to reduce to ethnic or racial demands. If the majority of the rioters are of Maghreb or African origin, some of them are Asian and French. This is also a movement irreducible to the category of youth, for the majority of the youth—unlike those of May 1968, or the demonstrations against the CIP in 1994, or the secondary school movement of last spring—have no associations there.

This is, moreover, a movement without spirit or class consciousness—a movement typical of those common uprisings that blur conventional distinctions: a movement of “imperative revolt” due to permanent poverty and daily humiliation. But it is also a movement without strategy, a movement more prone to gaze at itself on television screens, drawing its ephemeral strength from the media coverage it produces, and thus depending on the self-censorship of information put in place to avoid “the telethon effect.” It is a movement nevertheless more Luddite than playful, sustaining itself at the source of real despair, but lacking utopia, its horizon limited by bars and block towers.

For sociologists, journalists and certain revolutionaries, this movement is incomprehensible since it resists the well-oiled arguments they use to explain social movements: neither social analysis, nor the study of the composition of class succeeds in defining its specificity.

These riots are made by an unidentifiable mob—rebellious bodies whose existence is reduced to bare necessity, and who have not found any other language than that of destructive gestures.

Let us not fool ourselves; in everyday life many of this mob are detestable; some are numbed by religion, many alienated by consumerism, or enthusiasts of masculine values, sharing with the masters of society the stupid worship of sport (some riots were suspended during televised football games). Many are contemptible in their behavior toward women—whose absence in the riots signals an unacceptable limitation. Most of this mob would certainly not be friendly to us.

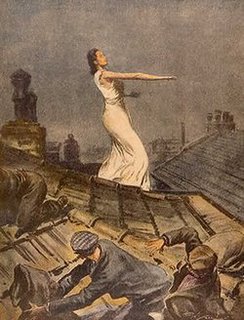

What is remarkable, however—beyond them—is their revolt. Through their actual contradictions, they represent the dark face of a vengeful social unconscious held back for too long, as those in bygone days representing the “dangerous classes.” But, at the risk of plunging back even more bitterly in their poverty, it will be necessary for them to draw on the lessons of their recent experience in order to gain lucidity. Already they have seen at work the repressive role of the imams and of Islam, mere auxiliaries to the police—as is all religion. This movement still has to get rid of all forms of puritanical and masculinist morality so that women will join them as equals—like the women fire-raisers of the Paris Commune in 1871—to take an active part in all future stuggles. Likewise, they must have done with the stupid gang rivalry that nails them to their “territories” and deprives them of a mobile offensive. And finally, they must learn to choose more directly political targets.

In a society in which all previous forms of belonging, and therefore of associated consciousness, have been wiped out, these events testify to the eruptive and uncontrollable return of the social question, firstly under an immediately negative form, that fire—emblem of all apocalypses—symbolizes. Indeed, unlike the rebellions in Los Angeles in 1965 and in 1992, the population of the districts here did not massively join the rioters. And in contrast to May ’68 neither poetry nor brilliant ideas are on the barricades. No wildcat strike is going to spread widely with these troubles. But the rulers have been given a good hotfoot and have been forced to unmask themselves.

A democracy which, in order to face up to a quantitatively limited movement (considering the number of participants), has been obliged to put back in force an old colonial law, but also to reveal its constituent deception: that is, where the police abuse their powers, the state of emergency gives to their abuse the legitimacy that it lacks. What we long ago called “individual freedom” is today known as the “discretionary power” of the cops.

In a flash, such warning lights have revealed—during these November nights—the return of a possibility that seemed to be lost: that of throwing power into a panic even when its forces are harassed in a disorganized manner through the whole territory by a handful of forsaken social casualties. From now on, we can imagine the strength of an uprising that would—beyond the inhabitants of the ghettos—include the whole population suffering from the rise of impoverishment, and would turn into civil war against the organs of capital and the state.

Beyond recent infernos presented as the very image of a nightmare, it is time that the dream of concrete utopia is raised anew.

The Paris Group of the Surrealist Movement

November 2005

Translated by Franklin Rosemont